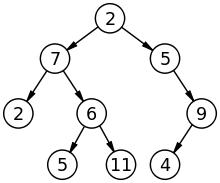

A simple unordered tree; in this diagram, the node labeled 7 has two children, labeled 2 and 6, and one parent, labeled 2. The root node, at the top, has no parent.

In computer science, a tree is a widely used data structure that simulates a hierarchical tree structure with a set of linked nodes.

A tree can be defined recursively (locally) as a collection of nodes (starting at a root node), where each node is a data structure consisting of a value, together with a list of nodes (the "children"), with the constraints that no node is duplicated. A tree can be defined abstractly as a whole (globally) as an ordered tree, with a value assigned to each node. Both these perspectives are useful: while a tree can be analyzed mathematically as a whole, when actually represented as a data structure it is usually represented and worked with separately by node (rather than as a list of nodes and an adjacency list of edges between nodes, as one may represent a digraph, for instance). For example, looking at a tree as a whole, one can talk about "the parent node" of a given node, but in general as a data structure a given node only contains the list of its children, but does not contain a reference to its parent (if any).

Definition

Recursive

Recursively, a tree is defined as a node (the root), which itself consists of a value (of some data type, possibly empty), together with a list of nodes (possibly empty); symbolically:

n: v [n[1], ..., n[k]]

(A node n consists of a value v and a list of other nodes.)

Note that this definition is in terms of values, and is appropriate in functional languages (it assumes referential transparency); different nodes have no connections, as they are simply lists of values. If the nodes are instead references to nodes (so one of the "nodes" could in fact point to an earlier node), one must specify that all the nodes are different, otherwise the above defines a directed graph,[n 1] possibly with loops.

Indeed, given a list of nodes, and for each node a list of its children, one cannot tell if this structure is a tree or not without analyzing its global structure and checking that it is in fact topologically a tree, as defined below. In terms of references, a tree is a special kind of directed graph, with a global constraint on its topology (namely no loops as an undirected graph).

Mathematical

Viewed as a whole, a tree data structure is an ordered tree, generally with values attached to each node. Concretely, it is:

- A rooted tree with the "away from root" direction (a more narrow term is an "arborescence"), meaning:

- A directed graph,

- whose underlying undirected graph is a tree (any two vertices are connected by exactly one simple path),

- with a distinguished root (one vertex is designated as the root),

- which determines the direction on the edges (arrows point away from the root; given an edge, the node that the edge points from is called the parent and the node that the edge points to is called the child),

together with:

- an ordering on the child nodes of a given node, and

- a value (of some data type) at each node.

Often trees have a fixed (more properly, bounded) branching factor (outdegree), particularly always having two child nodes (possibly empty, hence at most two non-empty child nodes), hence a "binary tree".

Terminology

A node is a structure which may contain a value or condition, or represent a separate data structure (which could be a tree of its own). Each node in a tree has zero or more child nodes, which are below it in the tree (by convention, trees are drawn growing downwards). A node that has a child is called the child's parent node (or ancestor node, or superior). A node has at most one parent.

An internal node (also known as an inner node, inode for short, or branch node) is any node of a tree that has child nodes. Similarly, an external node (also known as an outer node, leaf node, or terminal node) is any node that does not have child nodes.

The topmost node in a tree is called the root node. Being the topmost node, the root node will not have a parent. It is the node at which algorithms on the tree begin, since as a data structure, one can only pass from parents to children. Note that some algorithms (such as post-order depth-first search) begin at the root, but first visit leaf nodes (access the value of leaf nodes), only visit the root last (i.e., they first access the children of the root, but only access the value of the root last). All other nodes can be reached from it by following edges or links. (In the formal definition, each such path is also unique.) In diagrams, the root node is conventionally drawn at the top. In some trees, such as heaps, the root node has special properties. Every node in a tree can be seen as the root node of the subtree rooted at that node.

The height of a node is the length of the longest downward path to a leaf from that node. The height of the root is the height of the tree. The depth of a node is the length of the path to its root (i.e., its root path). This is commonly needed in the manipulation of the various self balancing trees, AVL Trees in particular. The root node has depth zero, leaf nodes have height zero, and a tree with only a single node (hence both a root and leaf) has depth and height zero. Conventionally, an empty tree (tree with no nodes) has depth and height −1.

A subtree of a tree T is a tree consisting of a node in T and all of its descendants in T.[n 2][1] Nodes thus correspond to subtrees (each node corresponds to the subtree of itself and all its descendants) – the subtree corresponding to the root node is the entire tree, and each node is the root node of the subtree it determines; the subtree corresponding to any other node is called a proper subtree (in analogy to the term proper subset).

Drawing graphs

Trees are often drawn in the plane. Ordered trees can be represented essentially uniquely in the plane, and are hence called plane trees, as follows: if one fixes a conventional order (say, counterclockwise), and arranges the child nodes in that order (first incoming parent edge, then first child edge, etc.), this yields an embedding of the tree in the plane, unique up to ambient isotopy. Conversely, such an embedding determines an ordering of the child nodes.

If one places the root at the top (parents above children, as in a family tree) and places all nodes that are a given distance from the root (in terms of number of edges: the "level" of a tree) on a given horizontal line, one obtains a standard drawing of the tree. Given a binary tree, the first child is on the left (the "left node"), and the second child is on the right (the "right node").

Representations

There are many different ways to represent trees; common representations represent the nodes as dynamically allocated records with pointers to their children, their parents, or both, or as items in an array, with relationships between them determined by their positions in the array (e.g., binary heap).

In general a node in a tree will not have pointers to its parents, but this information can be included (expanding the data structure to also include a pointer to the parent) or stored separately. Alternatively, upward links can be included in the child node data, as in a threaded binary tree.

Generalizations

Digraphs

If edges (to child nodes) are thought of as references, then a tree is a special case of a digraph, and the tree data structure can be generalized to represent directed graphs by removing the constraints that a node may have at most one parent, and that no cycles are allowed. Edges are still abstractly considered as pairs of nodes, however, the terms parent and child are usually replaced by different terminology (for example, source and target). Different implementation strategies exist: a digraph can be represented by the same local data structure as a tree (node with value and list of children), assuming that "list of children" is a list of references, or globally by such structures as adjacency lists.

In graph theory, a tree is a connected acyclic graph; unless stated otherwise, in graph theory trees and graphs are assumed undirected. There is no one-to-one correspondence between such trees and trees as data structure. We can take an arbitrary undirected tree, arbitrarily pick one of its vertices as the root, make all its edges directed by making them point away from the root node – producing an arborescence – and assign an order to all the nodes. The result corresponds to a tree data structure. Picking a different root or different ordering produces a different one.

Given a node in a tree, its children define an ordered forest (the union of subtrees given by all the children, or equivalently taking the subtree given by the node itself and erasing the root). Just as subtrees are natural for recursion (as in a depth-first search), forests are natural for corecursion (as in a breadth-first search).

Via mutual recursion, a forest can be defined as a list of trees (represented by root nodes), where a node (of a tree) consists of a value and a forest (its children):

f: [n[1], ..., n[[k]]n: v f

Traversal methods

Main article: Tree traversal

Stepping through the items of a tree, by means of the connections between parents and children, is called walking the tree, and the action is a walk of the tree. Often, an operation might be performed when a pointer arrives at a particular node. A walk in which each parent node is traversed before its children is called a pre-order walk; a walk in which the children are traversed before their respective parents are traversed is called a post-order walk; a walk in which a node's left subtree, then the node itself, and finally its right subtree are traversed is called an in-order traversal. (This last scenario, referring to exactly two subtrees, a left subtree and a right subtree, assumes specifically a binary tree.) A level-order walk effectively performs a breadth-first search search over the entirety of a tree; nodes are traversed level by level, where the root node is visited first, followed by its direct child nodes and their siblings, followed by its grandchild nodes and their siblings, etc., until all nodes in the tree have been traversed.

Common operations

- Enumerating all the items

- Enumerating a section of a tree

- Searching for an item

- Adding a new item at a certain position on the tree

- Deleting an item

- Pruning: Removing a whole section of a tree

- Grafting: Adding a whole section to a tree

- Finding the root for any node

Common uses

See also

Other trees

- DSW algorithm

- Enfilade

- Left child-right sibling binary tree

Notes

- ^ Properly, a rooted, ordered directed graph.

- ^ This is different from the formal definition of subtree used in graph theory, which is a subgraph that forms a tree – it need not include all descendants. For example, the root node by itself is a subtree in the graph theory sense, but not in the data structure sense (unless there are no descendants).

References

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Subtree" from MathWorld.

- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming: Fundamental Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89683-4 . Section 2.3: Trees, pp. 308–423.

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7 . Section 10.4: Representing rooted trees, pp. 214–217. Chapters 12–14 (Binary Search Trees, Red-Black Trees, Augmenting Data Structures), pp. 253–320.

External links